I am learning that freedom has its own rules.

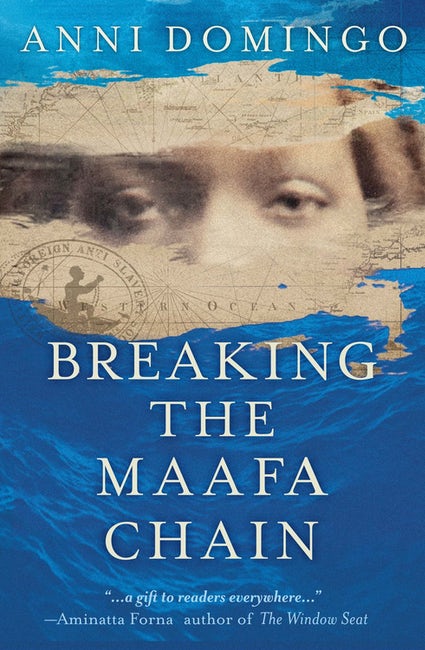

Breaking the Maafa Chain by Anni Domingo | Historical Fiction | Jacaranda Books | 336 pages | Review by Zahrah Nesbitt-Ahmed

History books give us insights into Sarah Forbes Bonetta’s remarkable life. The daughter of a Chief of a West African village, she was captured in 1848 by the King of Dahomey, and was later ‘rescued’ in 1850 by Captain Frederick E. Forbes of the Royal Navy. Captain Forbes was visiting Dahomey on a mission on behalf of the British Government of Her Majesty, Queen Victoria to negotiate clamping down on the slave trade. During his trip, King Ghezo (or Gezo) of Dahomey ‘gifted’ a young girl to Queen Victoria. She would later be renamed Sarah Forbes Bonetta – taking on Captain Forbes last name and his ship, the Bonetta. Sarah Forbes Bonetta remained in England, becoming the Queen’s ‘goddaughter.’ The Queen supported Sarah financially while she was under the care of the Forbes family. This was until 1851 when she returned to Africa, moving to Freetown in Sierra Leone to study at an all-girls’ missionary school.

There is more than this to Sarah Forbes Bonetta, but it is this part of her early childhood from which Anni Domingo draws inspiration in her debut novel, Breaking the Maafa Chain. Intertwining facts from Sarah’s life with fiction, the novel tells the story of two sisters, Salimatu and Fatmata, in the mid-nineteenth century. The sisters are captured from their homeland in West Africa and sold separately into slavery. Although slavery was abolished for over two decades at the time in which the story is set, the illegal capturing, buying, and selling of humans persisted.

Two Sisters: Salimatu and Fatmata

Both Salimatu and Fatmata may have both been ripped away from their family and the only life they knew at such a young age, but each sister has a different fate.

Salimatu, initially captured and held captive by the Dahomey Kingdom, eventually sails to England with Captain Forbes. In England, ‘Papa Forbes’ teaches her English and to read and write. He remarks on her intelligence and quick ability to pick things up, while simultaneously stripping her of her identity, including her language, Yoruba. Upon arrival in England, Salimatu, re-named Sarah, continues to have elements of her identity stripped away as she assimilates into the upper echelons of Victorian England society to become an ‘African Princess’.

Stories like this emphasize the importance of having narratives that don’t sanitise the horrors and brutalities of slavery.

It takes the reader longer to realise Fatmata’s fate once the sisters are separated. As the older sister, Fatmata does all she can to ensure they are not separated when they are initially captured. Despite her efforts, Salimatu is sent to England and Fatmata is put on board a ship sailing for the Americas, ending up as a slave on a plantation in North Carolina. Through Fatmata’s experiences, Domingo portrays the harrowing life of a slave. Fatmata is also stripped of her identity; like Salimatu, she is denied the use of Yoruba. She is also tortured, raped, and separated her children. Stories like this emphasize the importance of having narratives that don’t sanitise the horrors and brutalities of slavery.

Holding On: Do We Need New Names?

Forced to change their names to Faith (Fatmata) and Sarah (Salimatu) and adopt new lives, the two sisters do what they can to maintain elements of their identities and culture to find some form of freedom in a world ruled by slavers and colonisers that tries to strip them of their personhood.

Faith (Fatmata), being older and having a fighting spirit, seems to be the more strong-willed of the two. Fatmata holds on to her gri gri (a talisman filled with objects to keep her safe) and doesn’t forget her sister. Fatmata hopes that Salimatu is safe, wherever in the world she may be. She also maintains part of her culture by giving her children African names and marking them with symbols from her home to signify who they are and where they are from, despite being born on a slave plantation. While these are names she can never say out loud to others, she holds them close to herself. Fatmata also finds ways to keep herself informed – secretly teaching herself how to read and write – an act that could lead to severe ramifications if she is ever caught.

Sarah often buries Salimatu, the part of her that reminds her that she is African, and not a princess, as deep as she can.

Sarah (Salimatu) adopts similar strategies to her sister in order to hold on to aspects of herself. Like her Fatmata, Salimatu keeps her gri gri with her, though she keeps it hidden. She takes comfort in her facial markings and never forgets her older sister, who she is also always searching for.

Yet, she more than Fatmata, struggles to maintain her identity. Sarah fluctuates between wanting and not wanting to assimilate to English life. Domingo captures the internal struggles a child as young as Sarah would have faced between maintaining Salimatu and becoming an African Princess in Victorian England. Sarah often buries Salimatu, the part of her that reminds her that she is African, and not a princess, as deep as she can.

On Blackness

While there are glimpses of hope, joy, love, and even passion in Breaking the Maafa Chain, Anni Domingo sensitively captures the reality of life for Black people in the nineteenth century. She reveals in detail what it would be like to be a little girl yanked from her home and transported to riches in England as well as what it would be like to be a teenager, also yanked from her home, and transported to slavery in America. Though the two sisters ended up in two different countries, which on the surface had two contrasting laws on slavery, Domingo deftly shows us that neither sister is truly free; they have no rights and are beholden to the people that stripped them from the lives they knew.

While there are glimpses of hope, joy, love, and even passion in Breaking the Maafa Chain, Anni Domingo sensitively captures the reality of life for Black people in the nineteenth century.

REWRITE MEMBERSHIP

paypal.Buttons({

style: {

shape: ‘rect’,

color: ‘gold’,

…