She knew first-hand that the offense most punished by the state was trying to live free. To wander through the streets of Harlem, to want better than what she had, and to be propelled by her whims and desires was to be ungovernable. Her way of living was nothing short of anarchy.”

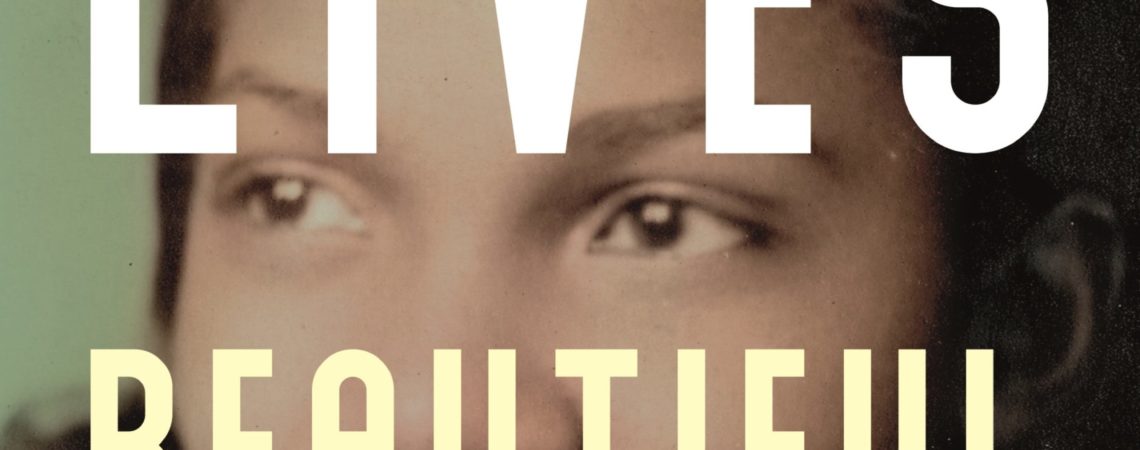

Wayward Lives, Beautiful Experiments: Intimate Histories of Social Upheaval by Saidiya Hartman | Nonfiction | Serpent’s Tail | 416 pages | review by Jenn Augustine

In her latest book, Wayward Lives, Beautiful Experiments: Intimate Histories of Social Upheaval, professor and 2019 MacArthur Fellow, Saidiya Hartman, explores the untold stories of young Black women who migrated to New York and Philadelphia from the southern United States shortly after emancipation. Based off archival documents, such as social work case notes, court transcripts, and photographs, Hartman creates a counternarrative to the pathologized poor Black girl that has been embedded in our society; Hartman reframes bad, immoral, and wayward behavior as beautiful experiments and true expressions of agency.

The False Promise of Freedom

In the early 1900s, Black folks in the southern US began migrating to northern cities, such as New York and Philadelphia, to escape the vestiges of slavery. Throughout Wayward Lives, Beautiful Experiments, Hartman tells the story of young Black women hoping to secure better opportunities and lead better lives in the north. Unfortunately, when they reach these cities, they find similar racial discrimination that they endured in the south. Black women were relegated to domestic work, were paid low wages, and were forced to live in segregated neighborhoods in poorly maintained apartment buildings with grossly inflated rents.

Any attempts to express agency, experience joy, or rebel against white middle-class social norms and values, were met with criminal punishment and interference from social workers.

Any attempts to express agency, experience joy, or rebel against white middle-class social norms and values, were met with criminal punishment and interference from social workers. Black women were often charged and imprisoned for prostitution with no evidence aside from standing outside after dark. Black girls and young women were detained even if they were not accused of a crime. The Wayward Minors Act, which disproportionately targeted Black girls and young women, allowed them to be arrested and sentenced up to three years in a reformatory for a non-criminal act but indicated potential future criminality. These non-criminal acts often were deviations from white middle-class, cisgender, heterosexual norms.

Subverting Social Norms

Despite knowing the risks, Black women continued to live their lives on their own terms, behaving in ways believed to be unbecoming of a lady. Black women went out dancing, had sex and bore children outside of marriage, and lived with men who were not their husbands. Hartman tells the stories of Queer Black women, openly loving other women, and defying gender norms. All of these assertions of agency were seen as direct attacks against the moral framework of the early 20th century and inherent failings of Black women, resulting in the downfall of the Black community.

Giving Voice to the Voiceless

By writing these Black women’s histories as narratives Hartman gives a voice to the voiceless. While some of the women discussed in the book are well known – Ida B. Wells, Billie Holiday, Gladys Bentley – others, such as May Enoch, Mattie Jackson, and Fanny Fisher, would remain unnamed, their stories untold if not for this book. Girl #2, General House Worker, and The Window Shoppers, among others, remain unnamed, however, Hartman is able to tell their stories. By telling these women’s stories, Hartman gives a voice to ordinary Black woman, their experiences, and marks them as important.

These women, their pain, their suffering, their joys, their pleasures, have been buried, and, when discovered, were masked by moral standards imposed upon them by their oppressors.

These women are not the folks we learn about in our history classes; these women are not the folks I learned about when I got a Master’s in Social Work. But I learned about Jane Addams, also featured in the book, a white woman, heralded as one of the mothers of social work, who believed that Black women were more susceptible to temptation than white women and that Black people required more regulation to be brought under social control. These women, their pain, their suffering, their joys, their pleasures, have been buried, and, when discovered, were masked by moral standards imposed upon them by their oppressors. Wayward Lives, Beautiful Experiments by Saidiya Hartman is complexly and beautifully written. It contains intimate portraits of the inner lives of Black women that have not been previously explored or examined. It is a testament to Black women’s resilience and our drive not only to live but to thrive despite the dearth of opportunities, the violence, the obstacles put in our way – despite the lack of recognition. Wayward Lives is a celebration of our waywardness and asserts that it is beautiful.

It is a testament to Black women’s resilience and our drive not only to live but to thrive despite the dearth of opportunities, the violence, the obstacles put in our way – despite the lack of recognition.

ZORA Online Course Feb 2024

ZORA Online Writing Course. Next course dates: 5th Feb – 29th Feb

Want to improve your writing but can’t find the time to attend a course? Our online creative writing course is perfect for busy and hectic lives. The assignments are sent to you every morning, so you can do them whenever and wherever you want!

<span s…