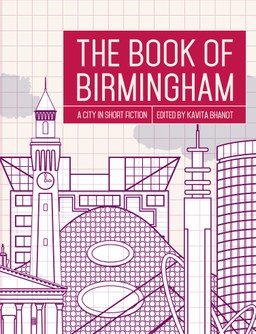

The Book of Birmingham: A City in Short Fiction

Editor: Kavita Bhanot

Featuring women of color authors: Jendella Benson, Kit de Waal, and Sharon Duggal

Publisher: Comma Press

Genre: Short stories, Fiction

Published: 2018

Page length: 192 (paperback)

Review by Jenn Augustine

“And yet, between my departure and my return the city had erected and destroyed several other iterations of itself. Builders had shifted their hands to tearing down that which they had not long ago completed. Birmingham is a true city of the future: endlessly becoming, never arriving.” – C.D. Rose, Necessary Bandages

In The Book of Birmingham, writer Kavita Bhanot expertly compiles a selection of thoughtful and compelling short stories about Birmingham, a major city in England’s West Midlands region. Each story is written by an author who has either lived or currently lives in Birmingham, which allows for an authentic, and accurate representation of the city. Three of the ten stories featured in the collection are written by women of color: Jendella Benson, Kit de Waal, and Sharon Duggal.

Each story in The City of Birmingham provides its own rich, textured, and complex history of the city post-WWII to the present

The collection broadly explores the themes of race and immigration, and class and industrial decline. When read together, the stories play off of one another, to tell a recent history of the UK’s second most populated city. Each story, ultimately, illustrates the changing face of Birmingham over time.

Immigration and Race

The collection begins with Kit de Waal’s Exterior Paint, which focuses on Alfonse Maynard, a Black immigrant from St. Kitt’s, as he reflects on his relationship with his late wife, a white woman, as he readies their house for sale. Central to Exterior Paint and other stories in the collection, such as Sharon Duggal’s Seep, are the disadvantageous and hostile experiences newly arrived immigrants face when interacting with their new surroundings – then, a predominantly white Birmingham.

Despite being called to the UK to help physically rebuild the country after World War II, immigrants were met with discriminatory housing policies and hostile social environments. They were forced to live in certain sections of the city; their new homes were cramped with upwards of five people living together in a room; they faced discriminatory labor and employment practices, working excruciatingly long hours in physically dangerous jobs for low pay; in addition, they faced discriminatory social policies such as segregated pubs.

Thoughtfully assembled, each story is well positioned, leading into the next, advancing the reader forward in time and allowing them to gain a deeper insight into the diversity of lives that have been lived in Birmingham.

The stories: Exterior Paint, Seep, Amir Aziz by Bobby Nayyar, and 1985 by Balvinder Banga, speak to immigrant responses to this mistreatment in their new surroundings. While some immigrants such as Bina’s mother and father in Seep, as well as the narrator and title character in Amir Aziz, try their best to avoid confrontation, others, such Suresh, a border at Bina’s parents’ home, express their anger at their abuse. This frustration ultimately culminated in uprisings and protests, showcased in 1985, which recounts the violence during, and in the aftermath, of what are referred to as the Handsworth Riots.

Class, the British Industrial Decline, and Development

The arrival of immigrants from former British colonies, who were primarily regulated to factory work, coincided with the British industrial decline. In Taking Doreen Out of The Sky by Alan Beard, the reader follows the narrator, Mark, the day he discovers the factory where he works is closing down, putting himself and the community he has created for himself out of work. The industrial decline paired with the belief that this influx of Black and Brown people were taking white working class jobs, lead to a growth in white supremacist groups, as seen in Joel Lane’s, Blind Circles.

The arrival of immigrants from former British colonies, who were primarily regulated to factory work, coincided with the British industrial decline.

From there, the stories in the collection focus on a different demographic, not of individuals who have lived in Birmingham for generations and have stayed, or immigrants who have come from former British colonies to a new home, but young people who have lived in Birmingham, left, and returned. As Bhanot states in her introduction, 40% of the residents of Birmingham are under the age of twenty-five. It is to attract these young, moneyed people that Birmingham continuously develops and redevelops “hoping,” Bhanot asserts, that the development “will finally enable Birmingham to live up to its ‘second city status”.

Each story in The City of Birmingham provides its own rich, textured, and complex history of the city post-WWII to the present. Thoughtfully assembled, each story is well positioned, leading into the next, advancing the reader forward in time and allowing them to gain a deeper insight into the diversity of lives that have been lived in Birmingham. The collection, additionally, enables the reader, even one who may be completely unfamiliar with the city (such as me, an American), to truly envision the changing face of Birmingham.

ZORA Online Course Feb 2024

ZORA Online Writing Course. Next course dates: 5th Feb – 29th Feb

Want to improve your writing but can’t find the time to attend a course? Our online creative writing course is perfect for busy and hectic lives. The assignments are sent to you every morning, so you can do them whenever and wherever you want!

<span s…