“What you see here, this nigger, killed himself,” Erasmus Wilde said. “He was my slave, and he has killed himself. He has therefore stolen from me. He is a thief.”…“I understand that some of you believe you will be reborn in your homelands when you die.”… “No man can be reborn without his head,” the master called out. “I will do this to each and every new suicide. Mark me. None of you will ever see your countries again if you continue to kill yourselves. Let your deaths come naturally.”

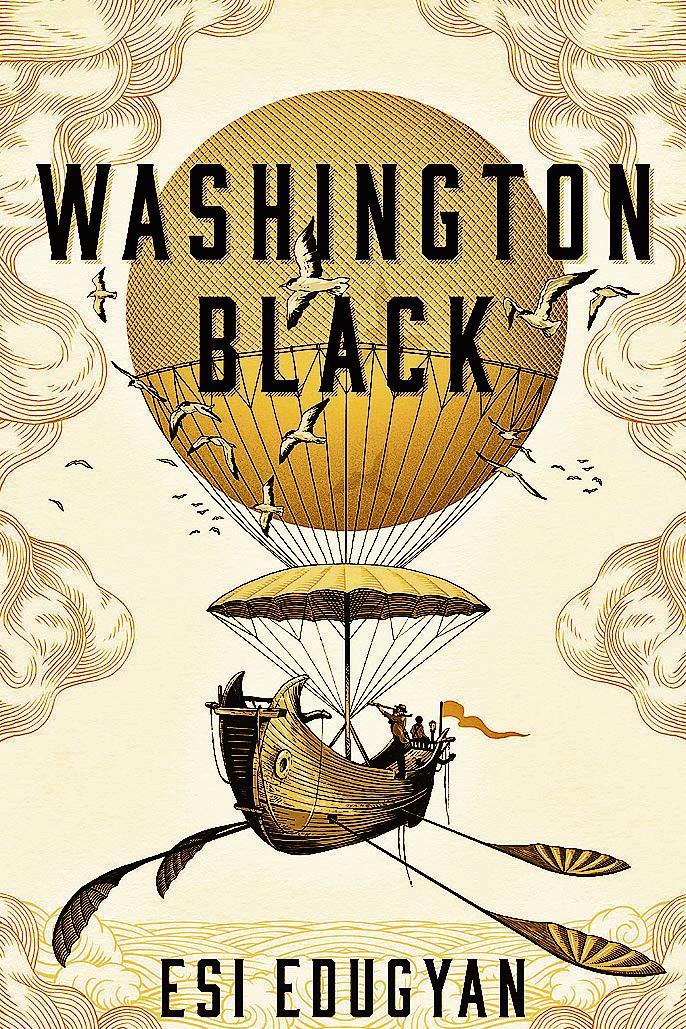

WASHINGTON BLACK by ESI EDUGYAN | HISTORICAL FICTION | 432 PAGES | PUBLISHER: SERPENT’S TAIL | Review by African Queer

Shortlisted for the 2018 Man Booker Prize, Washington Black by Esi Edugyan is a tale quite unlike its contemporaries situated in the slavery period. That Edugyan chooses to focus on the unlikely adventures and triumphs of an enslaved person sets it apart from other slavery narratives. Yet, this work remains fraught with some of the same problems that are inevitable in a tale about slavery; to give an enslaved person a life full of relative freedom does not automatically erase the time, place and ideologies within which this person exists, after all.

Edugyan painfully shows the reader that, under the circumstances of the time, freedom from slavery did not guarantee freedom from white domination

The book takes the reader on a journey through four continents. The titular character, Washington Black (Wash) is born an enslaved person on Faith plantation in Barbados, finding himself under the care of Big Kit, a mother figure. However, his life takes rather unexpected turns at a tender age, and these

The Intrusion of Whiteness

That Wash is enslaved creates the obvious scenario that he should come subservient to a white master. However, Edugyan painfully shows the reader that, under the circumstances of the time, freedom from slavery did not guarantee freedom from white domination. At the age of 11, Wash is taken under the custodianship of Titch, an abolitionist who wishes to construct a hot air balloon, ‘The Cross Cutter’, on Faith plantation. On the surface, it would appear on all accounts that Titch is humane and altruistic towards the young boy. It bothers Titch to see his brother treat the enslaved with such brutality, and it seems that he looks upon Wash as a friend and an equal. However, a deeper look into the relationship between the two reveals that, in reality, Titch merely views Wash as an accessory to his scientific endeavours, with the latter being light enough in weight to accompany Titch on the Cross Cutter without affecting its equilibrium.

Years later, when Titch and Wash have long been separated, Titch having literally run away from Wash, the latter travels to Morocco to reunite with Titch, whom he practically considers to be a father figure. Upon their reunion, Wash finds that Titch has taken another younger boy under his care in the same manner as he had done with Wash.

One aspect of the book that frightens in its accuracy is the level of violence that enslaved peoples must inflict on themselves and each other as a means of survival or escape

No doubt, Titch considers his actions in taking these young men in to be an act of benevolence. He believes himself to be against the principles of slavery and actively works against them. But Titch’s compassion is not pure. If anything, in his white

What is True Freedom ?

That Wash is free on paper does not grant him freedom in his existence. For years, he is tracked down by a slave catcher and is forced to live his life in a state of constant wariness. Even after he discovers his talents in science and scientific illustration, he must remain a secondary character to his own brilliance; a footnote in his own inventions. Across continents, his works are recognised, though not as his own, and his light dimmed even as he continues to display to the reader his prowess in the sciences.

The Multidimensional Violence of Slavery

One aspect of the book that frightens in its accuracy is the level of violence that enslaved peoples must inflict on themselves and each other as a means of survival or escape. That these people must suffer under the hands of masters and overlords is the bare minimum. From birth, Wash is forced to cope with the violence that is abandonment by his mother at birth, the breaking of his ribs by his loving custodian, and theft from fellow enslaved peoples in their bid to survive. However, no violence can overshadow the brutal belief held amongst the enslaved that the only way to true freedom is through death. Big Kit convinces Wash that they will be able to return to the land of their ancestors only if they kill themselves. Unfortunately, even this small grace is ripped away from them as evidenced in the opening quote above. Even upon death, the enslaved are allowed no repose as their bodies are mutilated to prevent return to the homeland.

Even upon death, the enslaved are allowed no repose as their bodies are mutilated to preventreturn to the homeland.

The adventures of Wash throughout the story, and the implausibilities therein, are perhaps the most masterful aspect of Edugyan’s work here. Even in the face of extreme violence and brutality, the author manages to concoct a tale that convinces the reader that a person once enslaved can go on to travel the world, excel in sciences once completely unknown to him and, ultimately, make advancements of his own in the scientific field. The choice by Edugyan to use science to tell this tale, despite the fact that the sciences are still an elite field that excludes Black people to this day, only adds to the feat that this work achieves, and provides great hope to young readers of colour.

ZORA Online Course Feb 2024

ZORA Online Writing Course. Next course dates: 5th Feb – 29th Feb

Want to improve your writing but can’t find the time to attend a course? Our online creative writing course is perfect for busy and hectic lives. The assignments are sent to you every morning, so you can do them whenever and wherever you want!

<span s…