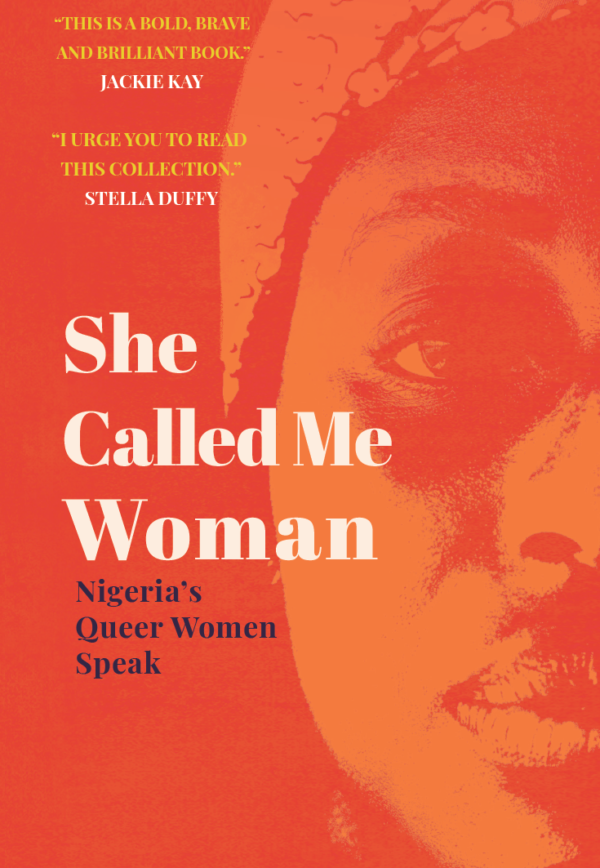

She Called Me Woman: Nigeria’s Queer Women Speak

Genre: Queer/ Non-Fiction

Editors: AZEENARH MOHAMMED, CHITRA NAGARAJAN, RAFEEAT ALIYU

Publisher: Cassava Republic

Review by African Queer

I do not believe that who I have sex with is part of my sexual identity. I am a queer woman and this is not because I have sex with other women…Being queer does not depend on whether I have sex with a woman or not. I am a constant

Africa’s foray into writing the secret stories of its pasts and presents is finally in full swing. Nigeria is certainly leading at the forefront of queer fiction, exploring different variations of queer relationships, and laying bare the visceral truth behind being queer in Africa. Now, queer non-fiction is also emerging on the continent and the larger Black diaspora and, once again, Nigeria is among those leading the charge with She Called Me Woman (SCMW).

The book takes the form of an anthology of personal accounts from Nigerian women – both cis and trans – living within and outside Africa. This statement alone shows how forward-thinking the book is, attempting to broach a topic that as yet remains a dead topic in much of Africa: that of being transgender. And so in this fashion, SCMW does more than raise consciousness on the plight of LGB (lesbian, gay and bisexual) people on the continent, but also exposes the reader to the lives and celebrations of queer women, both recognised and invisibilised.

Below are some aspects of the book that provoke thought, thereby making the book a vital resource in exploring ideas around queerness within the African context.

The current legal status of homosexuality in Nigeria

As it stands, the Criminal Code of Nigeria proscribes a maximum sentence of 14 years in prison for homosexual acts, which the Code terms as ‘carnal knowledge against the order of nature’, wording which is a relic from the country’s colonial past. This law is however explained by the society as being a consequence of the country’s upright moral code and subscription to religion, with majority of the country being Christian or Muslim.

The effects of this law were at first felt quite severely when it was passed, owing to the fact that it emboldened transphobes and homophobes to mete out violence against queer people who had previously lived in relative calm. The women tell of the apprehension and fear that they felt when the law was passed: BM (all identities are protected in the book) explains that in the past non-queer and queer people could interact freely with each other but now, with the passing of the law, any violence against women can simply be explained away by the perpetrator saying he was punishing the woman for being a lesbian. The law has not only illegalised homosexuality but has also legalised rampant criminality.

Homosexuality and the African family

The religious ideals held by those who support the law – as a sort of cognitive dissonance – are also shared by a good number of the women who tell their stories in the anthology. For some, their strong religious familial backgrounds and own personal beliefs bring much turmoil for them. 25-year-old ZH admits to being a staunch Christian who prays, reads the Bible and goes to church of her own volition. However, her family – who naturally introduced her to religion – cannot come to terms with her sexuality, and she later confesses that her father tried to kill her when he found out about her queer identity. For most families, it would appear that their adherence to their religion by far supersedes their acceptance of their own, and therefore precludes them from trying to understand their queer children and siblings.

There is also the added problem that, for those who feel at home in their religion, the churches and mosques no longer welcome them. TQ talks about the fact that she absolutely adores being a Christian and submitting to God in prayer, but that she now finds herself uncomfortable in church because the clergy is currently overly focused on preaching about the ills of homosexuality.

It’s just a phase

The outright denial by much of African society of the possibility of an African being homosexual, and the blatant rejection of it as being a consequence of Western influence, is a running theme of the book. Even more worrying though is the idea by those who are same-sex loving that what they are experiencing is just a phase, as this speaks to how much this belief that homosexuality is foreign can easily permeate into the psyche of the African homosexual. BM recalls a conversation with her mother in which the latter, while seemingly accepting of her daughter’s orientation, reassures her that the feeling will pass. This prompts BM to take a closer look at her mother and come to the realisation that perhaps her own mother had also in her youth felt the same way she now did but shoved these feelings aside in favour of the more conventionally accepted mode of living: where a woman eventually meets a man and settles down to build a family.

In a similar fashion, a good number of lesbian-identifying women in the book have been in relationships with men in an attempt to rid themselves of their feelings, while others bemoan the fact that they have been with partners who ended up leaving them in order to be with men, even though they did not want to be. The pairing of homosexual women into heterosexual relationships seems to act as a buffer from violence and a concession that the safest way is to conform. Some choose this path, while others opt to rebel and loudly stand in their truth.

The consequences of rejection

Some of the women confess to turning to a more-than-recreational use of drugs to cope with the rejection that they face from family and society. This has encouraged negative stereotypes that homosexuality is tied in with such habits as excessive drug taking and promiscuous sexual activity. A few of the women in the book also discuss the negative effects that rejection has had on their mental health. And this propensity to mental illness is not far from the truth. Statistics show that, across the globe, bisexual women are the demographic that suffer most from depression, and mental health within the LGBT+ community is a vital issue that often gets overlooked due to lack of visibility and poor access to healthcare. This, coupled with the fact that homosexuality is wholly illegal for Nigeria’s population, makes it virtually impossible to access the care needed to tackle mental illness within the community.

Emancipation

A running theme for all the women is the need for emancipation in order to live their lives freely and authentically. Some envision a future Nigeria in which same-sex relationships are no longer illegalised, while others hope to find a way to leave Nigeria and start afresh in more accepting countries. Other women simply want to be free from their families so that they can live in relative privacy. At the heart of all these dreams of freedom is one painful truth: that under the current circumstances, what is needed most by all these women – and indeed what makes it possible for some of them to lead their lives freely – is financial emancipation. Without adequate resources, options are pulled from under the feet of these women as well as other marginalised people.

It is worth drawing parallels between this anthology and Stories of Our Lives, a Kenyan anthology that was published in 2015 and also seeks to document the lives of queer persons on the continent. Both teach us that there is still much that needs to be done to fully decolonise and liberate the continent of archaic, colonial laws and embrace the true African history, which was accepting of all persons regardless of identity or presentation. Ultimately, however, these are stories of hope and triumph in the face of extreme oppression and hateful laws that seek to divide and dehumanise. These women have found the courage to speak truth to power in an environment where death is always imminent, and the world is better for hearing their voices where silence feels like the better option.

ZORA Online Course Feb 2024

ZORA Online Writing Course. Next course dates: 5th Feb – 29th Feb

Want to improve your writing but can’t find the time to attend a course? Our online creative writing course is perfect for busy and hectic lives. The assignments are sent to you every morning, so you can do them whenever and wherever you want!

<span s…