“As we have done with Mbuya Nehanda, the Mother of our Nation, the lone heroine of our Chimurengas, our political history is one that makes wombs of women, empties us of all human complexity, impregnates us with all that is good or wrong in our society so that women are either Mothers of the Nation, birthing all that is good, or Evil Stepmothers, birthing all that is bad in our society.”

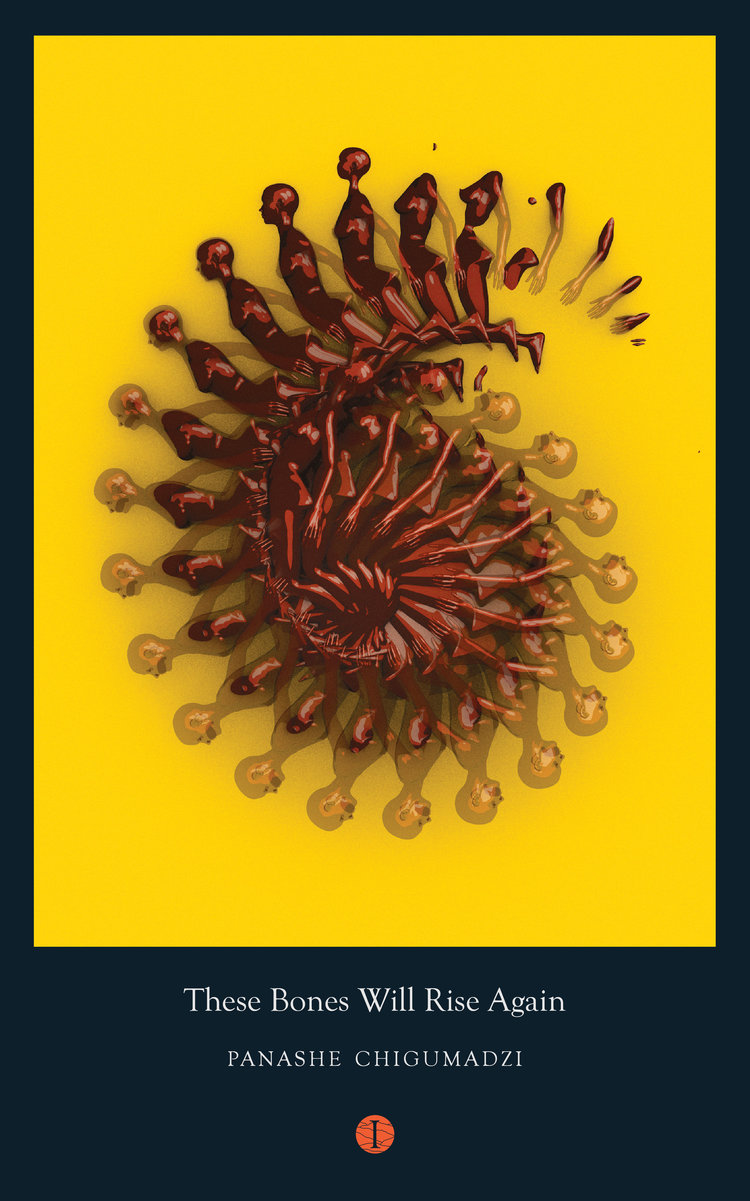

These Bones Will Rise Again by Panashe Chigumadzi | Historical Memoir | 144 pages | The Indigo Press | Review by African Queer

These Bones will Rise Again is the second offering from the Zimbabwe-born, South Africa-raised author, Panashe Chigumadzi. Presenting a searing account of the rewriting and erasure of histories surrounding the three Chimurengas (wars in Zimbabwe), the author has masterfully succeeded in providing the reader with a book that is a powerful ode to the various women, both great and small, who took Zimbabwe through its multiple phases of liberation. Below is a brief discussion of the thoughts and questions that most prominently stood out to me as I read this short yet highly enlightening book.

Women in the Struggle

The cementing of the place of women in the annals of history begins with (what is documented as) the first Chimurenga of 1897, when the spirit of Mbuya Nehanda, through a medium, puts up a spirited fight against the occupation of the British in southern Africa. It is this medium that, to date, is held up in Zimbabwe as having been the most valiant leader in the early resistance movements against colonisation. Yet, through Chigumadzi’s lens, we are able to view this glorification as both a positive and a flaw: the figure of Mbuya Nehanda through the 1897 medium (she is to manifest in several other media after that and is believed to have been manifesting since the beginning of time) not only freezes the role of women of the resistance in time, locking it firmly in the 19th century, but also ensures that any subsequent resistance action by women to date is vilified.

This resistance against the resistance of women is witnessed more clearly during the Second Chimurenga, which involved the fight for independence from the Rhodesian government. By this time, the movement of women in urban centres became heavily restricted, with insistence that women return to the villages in order to raise and take care of families. Women during this era not only had to fight against colonial occupation, but also against what Chigumadzi calls the African patriarchy. Quite discouragingly, these two oppressive forces were able to unite in their insistence that a woman’s place is solely within the family, thereby affirming the idea that even those who are oppressed would choose to unite themselves into a stronghold of greater oppression rather than work towards the liberation of any of those in the margins.

Mbuya Nehanda, too, suffered the same fate of relegation, being turned from a figure of strength and power into a ‘mother of the nation’. An imagining of Mbuya within the patriarchy could only have her be praised so long as she is seen as being a mothering and birthing figure.

She also calls to our attention the denigration of powerful women. Grace Mugabe, arguably the most powerful woman in modern Zimbabwean politics, was relegated to the position of a whore for daring to declare that she had her eyes on the presidency.

Peoplehood

It is not only through womanhood that erasure occurs, however. As with most other colonised countries, Zimbabwe was conquered because its various peoples were divided, leaving the Shona as the most prominent group of people. Chigumadzi points out the irony in this situation; considering the fact that the Shona themselves comprise of various other groups of people through marriages, migrations and other interactions. In spite of this, it is Shona history that is considered to be Zimbabwe’s history. The commemoration of the First Chimurenga of 1897, for instance, completely disregards that the Ndebele were also putting up fierce resistance against the British on their end. The later formation of the ZANU-PF, which rules into the present, and the genocide of minorities which remains unconfessed and unrepaired, both point to the continual dismissal of the personhood of the Ndebele, and other ethnic groups, as Zimbabweans.

The stripping off of personhood once again – and inevitably so, where oppression is concerned – extends to women. Beyond Mbuya Nehanda’s unspiritual freezing in time, hardly any other women are recognised as having contributed to the resistance movement. Yet, we know this to not be true. Reading the works of other feminist Zimbabwean authors such as Tsitsi Dangarembga teaches us that women, if anything, formed the front and centre of resistance. Chigumadzi on her part provides us with factual accounts that this was indeed the case. She also calls to our attention the denigration of powerful women. Grace Mugabe, arguably the most powerful woman in modern Zimbabwean politics, was relegated to the position of a whore (that this term is considered derogatory in the first place points to a much larger misogynistic issue) for daring to declare that she had her eyes on the presidency. Worse still it would appear that, like a sacrificial lamb, Grace Mugabe is slaughtered within the larger Zimbabwean consciousness and serves to wipe away all of Robert Mugabe’s sins by taking them on as her own.

Chinyakare and Chimanjemanje: The Battle Between the Old and the New

Colonisation is a season of rupture. It comes in to disperse and replace: cultures, beliefs, traditions, religions… Zimbabweans understand and pay attention to both that which has been dispersed, the chinyakare, and that which has come in to replace it: the chimanjemanje. Part of Zimbabwean resistance in fact involved balancing and hybridising the two. Chigumadzi points to the example that some of the most prominent churches in Zimbabwe are factions begun by indigenous Zimbabweans that combine both Christian belief and traditional religious belief. Indeed, it is these churches that the greatest political leaders turn to for predictions of their future leadership that can be believed by the citizenry. This hybridisation is the route to survival taken by a people who were under colonial oppression for so long.

Through her work, Chigumadzi endeavours to remind us that the place of women within society, try as we might to hide or destroy it, remains unbowed and all-powerful.

Perhaps what makes this book so impactful is the fact that Chigumadzi tells the story of Zimbabwe by telling her own story. The appeal of the book lies not only in the correction of historical errors but also in the journey that the author takes to do this. These Bones will Rise Again is not just historical but also historically autobiographical, with Chigumadzi learning about herself by learning about her lineage. Through her work, Chigumadzi endeavours to remind us that the place of women within society, try as we might to hide or destroy it, remains unbowed and all-powerful.

ZORA Online Course Feb 2024

ZORA Online Writing Course. Next course dates: 5th Feb – 29th Feb

Want to improve your writing but can’t find the time to attend a course? Our online creative writing course is perfect for busy and hectic lives. The assignments are sent to you every morning, so you can do them whenever and wherever you want!

<span s…